Hemp is a favorable addition to plant-based proteins. It is one of the fastest-growing plants in the world, and it may be less allergenic than other sources of plant protein.

An Impossible Burger from Trillium, lentil meatballs from Martha’s Café, and soy milk lattes from Café Jennie—plant protein is found almost everywhere on campus, offering more sustainable and healthy alternatives to traditional animal proteins. Three sources of plant protein currently dominate: soy, pea, and wheat. But recently, hemp has been added to the mix.

Hemp plants, like marijuana, belong to the cannabis family and produce compounds called cannabinoids. Under United States law, hemp is defined as having no more than 0.3 percent delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the most psychoactive cannabinoid. (In marijuana, concentrations of THC can reach 30 percent or more.) Nevertheless, hemp plants can be bred to produce other cannabinoids, such as the widely marketed cannabidiol (CBD).

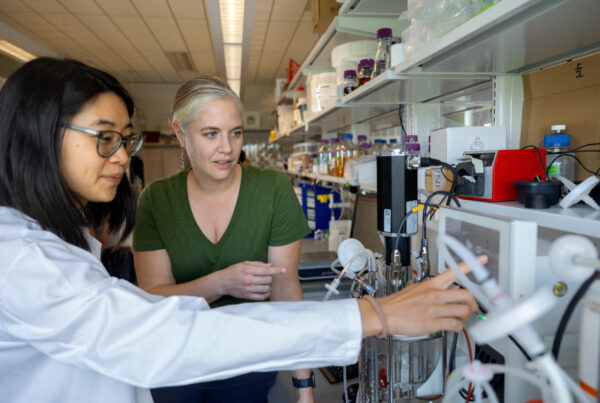

Hemp was federally legalized for research purposes in 2014and commercial purposes in 2018. Because its legalization is fairly recent, hemp has not been thoroughly researched. Ph.D. candidate Martin Liu is interested in how hemp might function as a food source, and particularly as a source of protein.

Liu’s research compares distinct strains, or cultivars, of hemp that are intentionally bred for specific characteristics. With each cultivar, he looks at the type and amount of protein found in the seed and other qualities affecting how it might be used as a food.

“Hemp can be bred for a whole variety of purposes. Some cultivars are best for cannabinoids, [others are best for] food products, and you can even grow hemp for fibers which can be used in construction materials. It’s a very interesting plant,” Liu says.

Learn more about Watch Out Chicken, Here Comes Hemp. (Cornell Research)